In his latest book, The Quicks, author ROBERT DRANE profiles the most successful, frighteningly-fast and dynamic Australian bowlers to ever terrorise other cricketing nations. In this edited extract, he takes a look at one of greatest – the man they call Pigeon…

Between the beanpole kid, sixth pick for the Backwater (no kidding!) under-16 bowling attack who left outback Narromine to live in a caravan in Sydney’s Sutherland so he’d be noticed by grade cricket selectors, and the fast bowler who, upon retirement, was often praised faintly as the Dr Beat of metronomes, there was the small matter of 563 Test and 381 One Day International wickets. The man they called ‘Pigeon’ was a conspiracy, because a good conspiracy says it’s one thing while it does another. Unless you risked being called a conspiracy theorist you’d never come close to understanding him, and unless you exercised suspicion it wouldn’t be possible to reconcile all the unremarkable descriptions of his bowling with his world-record wicket tally.

The labours of this monotonous try-hard yielded statistics exceeding those of any merchant of pure speed, or anything approaching speed, who ever hurled a red or white ball. In 2020 England’s James Anderson passed 600 Test wickets – remarkable for a fast bowler – yet his statistics in every country against every team are notably inferior, as is his bowling average of 26.67. Fast bowlers naturally become back worn and arm weary, but McGrath’s effort, before retirement at the age of 38, to hold his average at 21 despite bowling thousands more deliveries than Ambrose, Marshall and Garner, all of whom boasted a similar average, is astonishing. The perennial Courtney Walsh bowled 774 more deliveries, at a good average of 24.44. Pigeon’s strike rate was better than that of any much-honoured contemporary such as Kumble, Warne, Muralitharan or Pollock. Unlike many, he succeeded in every condition against all competition.

McGrath didn’t promise mayhem, had no flowing mane, bristling mo or colourful coif. No affectation, mere effectiveness. He didn’t seek to bowl with éclat, just plenty of élan. No flash, just dash. Movement. Momentum. He had a way of having them suspect he was up to something then making them feel like nutters for thinking it, before proving their first hunch correct. He made a batsman superstitious, knowing he was a member of the most superstitious fraternity in world sport. Cunning in so many ways, he’d be asking sly questions, making bold statements, tinkering with and sometimes shattering the minds of batsmen before a series even began – long before he’d put them to the sword for us to see, but always he’d persist in convincing them the real Glenn McGrath didn’t exist.

I once interviewed Pigeon for a book about the Australian Institute of Sport’s greatest alumni, and his entire shtick was flat-toned, guileless self-effacement. The hermeneutics of suspicion were in order if I was to avoid a whitewash. “I just bore batsmen out,” he said, ignoring the trifle of that record. This generation of batsmen, eh? So easily bored!

Those who actually did believe Pigeon – there are still many – didn’t seem to notice that the premier batsmen he routinely discharged early never stayed long enough for ennui to set in: a remarkable 225 of his Test wickets consisted of openers or first drops. He dismissed 104 for ducks, a world record. They were defeated not with outright speed, but promptly nonetheless. “I don’t move the ball about much,” Pigeon said, as though it was some kind of shortcoming. So there he was, genial, only too ready to cop any backhanded compliment from any old commentator on his soporific rhythm or lack of any discernible weapon, his incomparable record the pachyderm in the parlour.

“No, you don’t,” I agreed. “You move it just enough to get an edge, thump a pad or disturb the castle, that’s all. Any more is excess anyway, and I can see you’re not an excess man.” This seemed to give him a second’s pause. “It’s all in the execution,” he continued as if by way of explanation, and looked at me without saying more. Was this his own little private double entendre? Probably not, but maybe. Now he had me second guessing like some lackwit batsman!

Once selected for Australia, Pigeon took up residence in the so-called ‘corridor of uncertainty’ like Howard at Kirribilli, and came to know the joint more intimately than any bowler in history. He was a scrupulous and subtle host, doing just enough to charm his guests before they knew it even while broadcasting hostility, making them feel like that disoriented, duped Pommy in The Magus. Those batsmen who did abide a little would be driven crazy by the maddening repetition and mostly do his job for him, but sometimes they’d feel perfectly comfortable and that’s when the poor fools, beguiled by simplicity, were in most peril.

If any bowler needs convincing that the corridor, that batting devil’s triangle, is the place to be hanging out they might consider the calibre of the batting souls McGrath made his own. Sachin Tendulkar had Warne’s number but couldn’t even find one for McGrath, apart from a few notable exceptions. The prodigious Brian Lara would occasionally get his way but it sometimes proved just enough rope; McGrath lassoed him 15 times in Tests. In 2000 in Australia, Steve Waugh, who had a history of besting Lara at crucial times, determined the series outcome inside one session by prematurely replacing leg-spinner Stuart MacGill as soon as Lara arrived at the crease. Lara looked up to see his antagonist McGrath, ball in hand. Before the over was done, before he had a single run, he was gone; the Windies fell for 82. McGrath, who took 6/17 and had match figures of 10/27, removed him again in the second innings.

As for Mike Atherton – well, Pigeon swiftly hog-tied Athers 19 times in Tests. Kevin Pietersen? Their careers overlapped during 16 months that were always going to be stormy. McGrath dismissed him five times in eight Tests, but Pietersen had his moments. In Pigeon’s final Test, England’s resident ego, getting more insolent by the innings, decided to add ignominy to his farewell by walking down the pitch before he released the ball. He was removed in both innings.

Undaunted, Pietersen wanted to perfect his tactic in the following one-day series. He did. He failed better. Embarking on one stroll and looking to drive Pigeon over the fence, he got a short one. The broken rib immediately ended his summer. After play, as McGrath walked down the race, he attempted a pig-headed Parthian shot, yelling from the balcony that he couldn’t believe McGrath broke his rib with such a crappy delivery. Pigeon offered to sign his X-rays. Pietersen is lucky McGrath retired when he did as he was in danger of being consumed by a mortal monomania, like Ahab set on avenging the loss of a leg to the whale. The next time McGrath, his Moby Dick, thrashed his way his career might have taken an embarrassing detour.

Like good batsmen, these blokes will all say they relished the challenge. In fact, they hated facing Glenn McGrath. Fast bowlers devour his master classes, and his 8/38 at Lord’s in 1997 is used in workshops. The ground sloped left to right, looking from the pavilion end. He’d plonk it with precision into a spot outside off stump, and some would naturally dart in. He made others hold their line. Simple, and it got him man of the match three times in three appearances. McGrath took 36 at 19.47 that series.

In 1998, in arid conditions in which xerophilic Pakistanis thrive, he took 12 wickets in three Tests after a 10-month injury lay-off. Twice he removed Inzamam, and on two other occasions when he trapped him in front the umpire’s arm froze at his side – the Pakistan paralysis. But it was McGrath’s mugging of captain Sohail that led to the first series win since the 1950s. McGrath cared little for conditions or styles: he didn’t have preferences. Like boxer Vasyl Lomachenko, who shrugs indifferently when asked whether he prefers orthodox opponents or southpaws as he knows he has a method for everyone and the versatility to access it in an instant, McGrath had absolute confidence in his technique. Lara was, after all, one of history’s most accomplished mollydookers, and Sachin, a right-hander, was in Bradman’s top bracket.

“My strength was the mental side of the game rather than the skill side.” Deception! He was the textbook embodied. The secret to his art was like a secret to success so simple it’s invisible to most. Hidden in plain sight.

THE STATS

| Tests | 124 |

| Wickets | 563 |

| Average | 21.64 |

| Five wickets in an innings | 29 |

| Ten wickets in a match | 3 |

| One Day Internationals | Matches: 250 Wickets: 381 Average: 22.02 Five wickets in a match: 7 |

Planning and skill, driven by an unceasingly scheming brain, won Pigeon his victories. He was a man who didn’t hope: hope is what you have when you leave things to chance. Pigeon expected. He had a plan for every batsman that was always up for review, but his technique remained as simple as the song of a bird in a bower, nuanced for every shade of circumstance. He was no automaton – though, obviously, he didn’t mind anyone thinking he was – but it so often involved a high arm, the snap of a straight wrist, the ball rising to the top of off stump, just outside maybe, and ever so slight tunings if needed.

The punctilious Pigeon had an obsessive need to bowl every ball exactly where he wanted it to go and got very annoyed if, just once, it dared to err. It was as powerful an urge as T.S. Eliot’s compulsion to deliver exactly the right word, knowing if he won that ‘intolerable struggle’, poetry would come. Everything came back to control. The moment a batsman entered the arena, he’d already spent weeks in Pigeon’s surveillance state. Stored in his memory was every visual detail of every wicket he ever took, and for preparation he’d replay their innings against him on the monitor of his mind, rewinding, pausing and watching for anything he hadn’t noticed before. If he didn’t punish his detainees early, there was a penalty for enduring: he’d subtly stalk them until they went barmy. Like any good dictator he kept them off balance, confused one moment, cocksure the next, until slowly they began to notice a suffocating pressure.

Pigeon’s long run would begin in the lead-up to a series. If it was a home series it began not long after the hapless opposition landed, so they could read him in the papers. First he’d tip a 5-0 result for Australia. He’d deviate from that occasionally – if it was a three- or four-Test series instead of five. Then he’d analyse the opposition’s weaknesses with brutal frankness – nothing personal, he’d just call a rabbit a rabbit.

Then he’d decide who his bunny was going to be: usually their best batsman and/ or captain. That was frequently accurate. He was a country boy who was partial to a wry ribbing, but he was only half-joking. Sometimes he’d go a step further and predict how he’d get them out. When a man actually goes ahead and achieves it, you don’t doubt his ability. Needless to say, Australia loved Glenn McGrath.

Pigeon had no claims to batsmanship, but when it came to understanding a batsman’s mind he was cricket’s Patrick Jane. He knew what technical strengths the man with the willow would lean on and understood how to turn his strengths to weaknesses. He was so good a cricketing mentalist he knew how to make a batsman think his weakness was a strength. He knew what a man would resort to, and when he would do it. Once in a TV interview with old skipper Mark Taylor before a Perth Test, Tubby innocently asked Pigeon, who was on 298 Test wickets, if he was hoping to get his 300th in the match. Hoping? Pigeon expected! He went one better than predicting he’d reach that milestone: he told Taylor he’d make the mark that little bit more special and declared Brian Lara number 300 after he despatched Sherwin Campbell.

Then he carried it out: Campbell, caught, and Lara becoming the middle victim – victim 300 – in a hat-trick.

Australia loved Glenn McGrath because he was there at the renaissance. Though ‘beating the Poms’ was spoken of as Australian cricket’s ultimate achievement, the West Indies were the true prize. Since Australia’s sudden decline in the early 1980s, the unopposed Caribbean champions enjoyed such hegemony it was pointless playing them if you had an aversion to getting hurt or humiliated – if you had a pulse, in short, and wanted to keep it.

Mark Taylor’s team arrived unheralded in 1995. By the first Test, their bowling unit looked shabby after front liners Craig McDermott and Damien Fleming suffered injuries. Neither side batted well. The Windies’ powerful attack still featured Ambrose and Walsh, and their batting included Lara, Jimmy Adams, Keith Arthurton and Richie Richardson. The ragtag Aussie attack was doing something right, though: the Windies batsmen were unusually quiet. McGrath’s spells at the crease were spells of another kind. Under Taylor’s enlightened leadership, planning and implementation were crucial.

The plan was simple, and young Pigeon, whose experience consisted of a handful of unimpressive Tests, carried it out better than anyone. His 17 series wickets seem ordinary but, well, it was all in the execution. The plan called for Lara to get full or wide balls, to be caught on the back foot. McGrath got him twice and subdued him. Angled deliveries would prevent the brilliant Richardson flaying the errant ball to the off side. McGrath served them to perfection. The tail were to be unsettled and launch no comebacks. McGrath had the attitude and the tools, bouncing the world’s most dreaded fast bowlers heedless of retribution. He was man of the match in the 10-wicket first-Test win.

Etched in my mind is an iconoclastic image: after making the vengeful Ambrose duck for cover, McGrath walked to his mark past the non-striker, Walsh. He was Walsh’s height – 6’6” (198cm) – and eyeballed him. He was a quiet young man then, so the defiance in his grin as he held Walsh’s gaze was conspicuous. Equally tall Brendon Julian, enjoying a brief time in the sun, did similar. Australia had fast men capable – at last – of looking the lofty Windies quicks in the eye, literally and figuratively. A poignant image of wounded pride was Walsh strutting with comical bravado to the crease, last man in, in the final Test. The Windies were about to lose their first series in 15 years. Walsh tried to make it look as though none of it mattered. It mattered. That series didn’t just end an empire; it caused tremors so deep Caribbean cricket never quite rebuilt.

Before the thrilling drawn 1999 series in the Caribbean, McGrath, by now the Aussies’ official propagandist (a role later filled by David Warner), publicly said in a routine prediction of doom that it was easier to beat West Indians than anyone else once you cracked the formula: “More often than not, something will happen if you wait.” His leaflet drops all had a similar message: “It’s no use. Give up. We have your leaders in our sights and they will betray you. Watch them run away.”

Great though McGrath was individually, he was enhanced greatly by symbiotic relationships. Taylor and Waugh used him well, and his partnership with Jason Gillespie constituted one of Australia’s best-ever fast-bowling combinations. Between them, he and Warne snared a staggering 1,271 Test wickets. Together they were lethal, and these two supreme bowlers didn’t just work according to a plan: they quickly computed the batsman’s. Individually they were brain busters. Together they made even the clearest-headed batsman believe his lunchtime cuppa had been spiked with DMT.

They understood the merits of pressure. They’d work on conceding a miserable three runs an over, two coolly quick minds sensitive to a batsman’s need to score. Two simple, repeatable actions from which subtleties would emanate; two apex predators insatiable for prey. McGrath said, “There’s a stat that says if you bowl three maidens in a row the chance of getting a wicket goes up incredibly. So it’s about control, bowling where you want to bowl, a partnership with the guy at the other end.” Information like that was never going to escape a tyrant like Pigeon. In the 2001 Ashes in England, he and Warne each exceeded 30 wickets. His method made him formidable in the short forms.

At the time of his retirement, his 7/15 against Namibia was the best bowling return in a World Cup match and second best in all ODIs. He also held the record for most wickets in one World Cup tournament (26 in 2007) until it was broken by Mitchell Starc in 2019, and he remains the highest overall wicket taker in World Cup history.

Two years after he retired in 2007 the devil was released for a little season of mayhem, a reminder to the current generation. Playing for an all-stars team packed with old teammates, he bowled to a new kid named David Warner, who’d raced to 15. Pigeon and Warne, who stood at first slip, were wired up and bantering with Mark Taylor in the commentary box, unheard by Warner. Taylor joked that he thought he caught McGrath swinging the ball, something McGrath will always deny strenuously. He laughed: “I’ve never tried to swing it.”

Then, disregarding Warner’s reputation as a formidable thrasher, he predicted how he’d dismiss him next ball: “Hopefully this will deck across and a catch to Warney would be nice.” Pigeon hauled his few extra pounds of avoirdupois to the crease. It decked across. Warner, thinking it was coming on, straightened up and stabbed at it. Sometimes Pigeon got it wrong – the edge went to Gilly, not Warney.

We remembered what we’d lost. Needless to say, Australia loved Glenn McGrath all over again.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

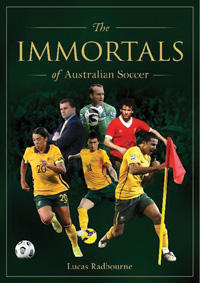

Lucas Radbourne thinks he could have gone pro if it hadn’t been for his bad knee. Instead, he settled for being an editor for FourFourTwo Australia, FTBL, The Women’s Game and Beat Magazine. These days he’s planning to spend most of his money on booze, birds and fast cars. He heard once that the rest you just squander.

The Immortals of Australian Soccer by Lucas Radbourne (published by Gelding Street Press, rrp$39.99) is available at all good book stores or online at geldingstreetpress.com

For the full article grab the November 2022 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.