With huge crowds, multi-million-dollar TV rights deals and generations of household megastars the V8 Supercars have been a huge local motorsport success story for over a quarter of a century, turning it also into a globally recognised phenomenon. In this edited extract from his new book, LUKE WEST gives us a taste of the comprehensive and absorbing history he’s compiled about this uniquely Aussie sport…

2020: A SEASON LIKE NO OTHER

General Motors’ announcement on February 19, 2020 that it would retire the Holden brand from the Australian market by year’s end came just two days before the Supercars hit the track at the season-opening Adelaide 500. Although Holden’s sales had plummeted since local manufacturing had wound down in late 2017, the news still seemed to take many by surprise. Especially those unaware that Holden had been wholly American owned since 1931! The company’s ‘football, meat pies, kangaroos and Holden cars’ advertising campaigns had obviously been successful, effectively brain-washing generations of Australians. If only they knew that GM had previously used the same campaign in its home country with catchy ‘baseball, hotdogs, apple-pie and Chevrolet’ theming. The decision by Detroit’s angels of death meant season 2020 would be the last featuring Commodores officially supported by Holden and representing the brand.

By necessity, some very big changes were coming to Supercars competition in the near future, quite apart from the regular off-season moves that were in evidence in the Adelaide parklands. Kelly Racing parked their four-strong fleet of Nissan Altimas for 2020 in favour of running a pair of Ford Mustangs. Rick Kelly and Andre Heimgartner stayed on to drive them, while Simona de Silvestro and Garry Jacobson departed. The ‘Swiss Miss’ left the series, while Jacobson moved into a Commodore at the expanded Matt Stone Racing.

Meantime, Tekno Autosports relocated from Queensland to Western Sydney and expanded to a two-car operation under the Team Sydney moniker. On the driver front the changes were many. Most notably, James Courtney and Scott Pye had left Walkinshaw Andretti United for, respectively, Team Sydney and the expanded Charlie Schwerkolt Racing. Replacing them were Chas Mostert and rookie Bryce Fullwood, the latter stepping up to the big league fresh from winning the Super2 title.

Mostert’s spot at Tickford Racing was taken by the driver with a last name that suggests he could be a distant French relative of a certain nine-time Bathurst winner — Jack Le Brocq. Meanwhile, Todd Hazelwood moved to Brad Jones Racing from MSR, replacing Tim Slade, who would snare the coveted part-time role at DJR Team Penske, co-driving for reigning series champion and Bathurst 1000 winner Scott McLaughlin. When cars blasted off the start line for the season’s first race on February 22 it was Jamie Whincup, the most successful Holden driver in ATCC/Supercars history, who landed the first blow.

From pole position Whincup led the field a merry dance to take the win in Saturday’s 250km leg from McLaughlin and Shane van Gisbergen. The main excitement was provided by Mostert, Cameron Waters and Will Davison, who engaged in some spirited and entertaining racing as they scrapped over sixth position. On Sunday, McLaughlin stormed into the lead from the start but was jumped by van Gisbergen when the two Kiwis both pitted at the same time for the first of each car’s two compulsory stops. The Triple Eight crew undid the advantage they gave their man on #97’s next stop by failing to add a full complement of fuel.

In the end, it was all academic, as van Gisbergen stopped on the track late in the race and failed to finish. Posting a DNF at the season opener is never ideal, but, although nobody knew it at the time, 2020 would prove to be an especially bad season for that to happen. McLaughlin won Sunday’s race from Mostert, Waters, David Reynolds and Whincup. The reigning champion’s title defence was off to an ideal start. It was going to take a major and unexpected development to usurp news of Holden’s demise as the talking point of the 2020 Supercars season, but then the COVID-19 virus arrived in Australia to become the defining facet of the season.

Teams rocked up to Albert Park in mid-March to perform their role as the prime Australian Grand Prix support act, but only hit the track to qualifying on the Thursday before the meeting was cancelled after members of the Formula 1 paddock tested positive for the virus. The pause-button was pushed on the season as the country (and the world) went into lockdown, only resuming at Sydney Motorsport Park in late June. In between was a barren period of much uncertainty, with only eSports filling the void of actual on-track competition.

Concerns about the viability of several teams emerged, especially when Milwaukee Tools abruptly ended its sponsorship of the Phil Munday-owned 23Red Racing. This put Will Davison out of a drive as Munday, in turn, pulled the pin on the Tickford Racing-run Mustang program. Munday’s Racing Entitlement Contract (effectively the ‘franchise’ to be the grid) was taken over by Boost Mobile owner Peter Adderton, who installed James Courtney in the driver’s seat. Penrith-raised Courtney moved across from Team Sydney, a switch that would see him slowly rise up the grid.

Many observers expected 23Red’s demise to be the first of several Supercar COVID casualties, yet when teams assembled at Eastern Creek in late June, the Milwaukee/Munday/Davison entry was the only real ‘team’ to fall prey to the tougher economic times. Alex Davison took Courtney’s spot at Team Sydney. While other domestic sporting organisations dithered — the Australian Rugby Union and Football Federation Australia’s A-League among them — Supercars emerged from the COVID suspension period smelling of roses. Much positive PR was generated through teams’ ability to build ventilators and other medical equipment.

Overall, the Supercars circus responded brilliantly to the COVID disruption, deftly side-stepping the many Government restrictions to put together a revised but credible Championship that encompassed 10 weekends of racing with several double-headers. It was by no means easy, but the sport found ways to get back on the track to fulfil sponsorship agreements and television contracts. Hardest hit were Victorian teams, which accounted for half the grid, with crews forced to hit the road for four months to avoid border closures and quarantining. Over 100 personnel would not see their loved ones in person between late June and late October!

All events between the Adelaide and Bathurst bookends featured a revised two-day format featuring a trio of races, each a whisker under an hour in duration. Coupled with a more liberal allocation of soft tyres, the reworked format proved a winning formula with more entertaining racing and a bigger spread of victors. Four venues hosted back-to-back rounds: Sydney Motorsport Park in June and July, the second featuring racing under lights; Darwin’s Hidden Valley in August; the Townsville street circuit in August and September; and The Bend Motorsport Park in September. Falling by the wayside were events in New Zealand, Tasmania, Western Australia and Victoria (Winton and Sandown) on permanent circuits, plus the Gold Coast and Newcastle street circuits. It was not just stopping the virus’ spread that scuttled the latter two, as the high cost of setting up temporary layouts could not be recouped with limitations in place on paying spectators.

If there was a positive to come from COVID, it was the opportunity to reinvent the racing. There was a new focus: fan entertainment rather than striving for technical excellence, what was increasingly being labelled ‘engineering masturbation’. For far too long Supercar racing had become an exercise in allowing the richer teams to spend big on personnel and equipment to make the cars faster with no tangible benefit to the quality of the show.

Restrictions on the number of team personnel permitted trackside saw refuelling disappear. Supercars, either by good luck or good management, found that their new format worked a treat at Sydney Motorsport Park with increased overtaking and more teams in the mix for victories. Brad Jones Racing’s Nick Percat returned to victory lane at each of the two SMP weekends after something of a dry spell, while Tickford’s Le Brocq scored a debut win at the same venue.

Meantime, a new name was etched into the Holden history books as a race winner after Erebus Racing’s Anton de Pasquale prevailed in the first of six sprints in Darwin. Whincup and van Gisbergen scored six wins between them through the sprint race portion of the schedule, the most memorable of these coming in Townsville when the New Zealander pulled a cunning move on race leader McLaughlin that allowed Whincup to pass #17, too.

Yet throughout the season the DJR Team Penske team leader was by far the most frequent winner and he marched to the title, wrapping it up on the second weekend of The Bend’s double-header. That same weekend saw Waters post his first win in a single driver race, to complement his Sandown 500 triumph with Richie Stanaway a few years earlier.

With the title fight done and dusted with a round to spare, crews headed to the Bathurst finale in October not having to worry about accumulating championship points. It would be a straight battle for the honour of winning the 2020 Great Race — the last featuring Commodores supported by Holden. Ford teams dominated practice and qualifying, with the Mustangs seemingly better suited to Mount Panorama’s high-speed corners. That’s exactly how the first couple of hours of the Great Race panned out, too, with McLaughlin and Waters leading the field under threatening skies. The likelihood of a fairy tale final factory Holden team win nosedived when Whincup made an uncharacteristic error while passing another Commodore, car #888 crashing spectacularly approaching The Cutting.

The order was quickly reshuffled when the heavens briefly opened with 50-odd laps in the books, van Gisbergen forging his way to the front. And that’s where he and co-driver Garth Tander stayed for the final 100 laps. They held out a flying Waters/Will Davison–driven Monster Energy Ford to record a memorable victory. Mostert and Warren Luff completed the podium for a Commodore 1-3. None of this trio of cars put a wheel wrong all day. It was just that SVG, GT and Triple Eight were marginally fastest of the faultless! It’s difficult to recall another Bathurst where so many cars ran so strongly without incident. There was no slipping off the track or slipping up in the pits for the frontrunners.

Any other year Waters and Davison’s stunning performance would have netted them a Bathurst victory. Like the ultimate winners, they were brilliant all day. It’s just that car #97 was minutely quicker over a longer run. McLaughlin and Slade’s fifth place was little reward for a very professional job. The #17 Mustang’s plan to ‘go long’ on fuel – thereby theoretically benefiting from a shorter final pit stop — was scuttled when the safety car appeared before Slade had completed the minimum number of laps for a codriver, forcing him to do an extra stint while SVG was in car #97. The timing was sheer bad luck for Team Dick.

In the end, Bathurst 2020 was won by the fastest car, drivers and team over 1000 kays. You can’t really ask for more than that. When van Gisbergen stopped on Mountain Straight on his victory lap to grab a Holden flag from a fan, holding it aloft through his partially opened driver’s door, he created a Kodak moment that will live in history. A 34th Great Race victory was a fitting way for Holden to officially end its 52 years of involvement in the Bathurst classic and touring car racing generally.

The season-ending Bathurst weekend also saw the launch of Supercars’ Gen3 rules, with the announcement that Chevrolet Camaro will replace Holden Commodore for 2022 as the category moves to two-door coupes from four-door sedans. General Motors has given its blessing for Supercars teams to use a facsimile of the road-going Camaro bodywork draped over a new control chassis. There was also a suggestion that the entity that will take over distributing General Motors models in Australia, GM Specialty Vehicles, will provide a degree of assistance to teams racing the bowtie brand. We’ll see…

Supercars worked hard to get Camaro over the line for 2022. Doing so was an existential mission, given that approximately two-thirds of its fanbase identify as Holden fans. It simply cannot afford for this core segment of its audience to drift away. It’s banking on Commodore diehards transferring their allegiance to a different subsidiary of the American giant, even though many Holden fans were blissfully ignorant of their beloved brand’s true ownership. Loud V8s and rear-wheel drive will remain the sport’s foundations, but with provision for electric-assisted hybrid power systems in the future to make it more attractive to new marques. Supercars says the aim of Gen3 is to enhance the racing spectacle, make building and running them more affordable for the teams and improve the visual appeal of the cars by making them look more like the road cars. The latter is to avoid the deformed look of the existing Mustang racer. Just how the future unfolds — and which manufacturers and models will be involved — will be fascinating to watch. ■

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Luke West is a life-long motorsport tragic and Australian motoring historian with an eye for colourful characters, quirky content and significant moments. He spent eight years as editor of Australia’s favourite retro motoring magazine, Australian Muscle Car, which followed a stint at Auto Action. He spent several seasons as a V8 Supercars oncourse announcer, including twice anchoring the Bathurst 1000 PA commentary team, and has also dabbled in TV commentary.

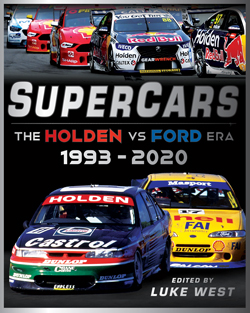

Supercars: The Holden VS Ford Era 1993-2020 (Gelding Street Press $39.99rrp), edited by Luke West is available from July 7 where all good books are sold

For the full article grab the August 2021 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.