The true story of a W.A. man’s life above the outback and how his true Australian Spirit helped him overcome adversity…

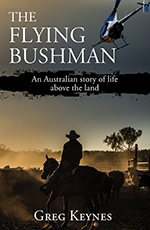

Growing up on the family property in outback W.A., Greg Keynes’ childhood seemed idyllic. Poignant memories of exploring with his dogs; hunting, working and joking with the local Yamatji people. Breaking free from family ties as a young man, Greg began his own aerial mustering business and fell in love. Life was sweet, until a routine muster in the rocky gorges of the Hamersley Range went horribly wrong and Greg faced the reality that he may never walk again. In this edited extract from his new book The Flying Bushman Greg takes us through his helicopter accident and surviving the near-death experience.

When you learn to fly a helicopter you quickly realise that in comparison to a fixed-wing aircraft they don’t glide well in the event of engine failure. However, there is an engine failure procedure that you can follow, providing you have enough forward indicated air speed and/or height above ground level up your sleeve. The manoeuvre is called “autorotation”, which involves keeping the main rotors turning by using the air moving up from underneath as you descend. It’s the equivalent of gliding in a fixed-wing aircraft. It allows you to keep some control over the direction you’re heading in, as the main rotor drives the tail rotor. I was very fortunate that my instructor had made me practise autorotations to the ground from thousands of feet. It gives you plenty of time to feel like messing your pants, but also sets you up for a real-life emergency.

I was 150 feet (the height of a 15-storey building) above ground level when my engine failed. I had no power to inject into the crippled machine, and could only use the cyclic to guide it to the best available landing space and hope for the best. I headed for the base of the gorge, and then it was as if everything slowed down to a snail’s pace. But I do remember the point of impact as my machine and I collided with the ground.

It was a huge impact. The new world I was in was taking me into another dimension. I was no longer in charge of what was occurring or where I was going, and yet the amazing thing was that it was so peaceful.

There was no pressure. I could take it easy and relax. I didn’t know what the end result would be, or what was in train for me, but I knew I would be taken care of. This was a beautiful, peaceful place, a lovely space to stay. And all the while there was an intense white light drawing me toward it. I had absolutely no control. The light was so powerful I felt I needed to shade my eyes. I remember thinking this must be heaven. But I was unable to confirm who or what was radiating that light and love — beautiful love. Even so, I was hanging back saying, “No, I don’t want to go. I’ve got too much to do. I don’t want to go.” It would be a conversation that would embed itself into my brain for the rest of my life. But I was not sure that I was actually saying the words. It was like somebody was saying them on my behalf. Like a prefect defending a bad pupil in a meeting with the headmaster, and making a case for a second chance.

I was getting awfully close to the light now, on my slow, unstoppable journey. I desperately kept repeating my mantra. The closer I got, the harder I seemed to pull back. I felt that once I came into the direct presence of that powerful light, I couldn’t go back. Well, someone must have been listening.

“You’ll be right mate.” Rodney’s voice brought me out of my meditative state. It was like coming out of a powerful dream after taking morphine. Then pain cut in and jerked me back to reality. Rodney Rodney [fellow cattle musterer mate] was trying to move me and I couldn’t seem to move my legs to help him drag me away from the demolished aircraft. The impact had smashed me into the seat, which had collapsed under the force. A large rocky outcrop had disintegrated my undercarriage, suspension and skid gear. The heels of my RM Williams boots had been torn from their uppers and my feet had gone through the front Perspex. The helicopter, usually 2.5 metres high to the top of the rotor blades, was compacted to less than a metre high, and I was buried in what was left.

Rodney must have been concerned about the threat of an explosion. The Robinson R22 helicopter has a gravity feed fuel system. The fuel comes from a tank that’s directly under the main rotors and flows down to the motor underneath. In this crumpled mess I was entangled in, the fuel was dripping onto the hot motor. Now that I was back in the real world, I could understand his concern. By the time the ground crew got to me and Kim [Greg’s wife] arrived, Rodney had dragged me away a little distance from what was left of the aircraft and laid my head on his coat. There were lots of rocks around and there was nowhere that was really flat.

Lionel Ainsworth from Red Hill Station sat cross-legged all night, some 10 or 12 hours at least, with a pillow on his legs, so that I’d be able to rest my head and keep slightly elevated as they didn’t know the extent of any internal injuries. Kim was obviously horrified at what she saw, and tried to comfort me as best she could. But it was a long night. The only painkillers available were two paracetamol tablets somebody had in their saddlebag.

The RFDS arrived in the morning, with Rodney guiding them in. Once the doctor had examined me and administered a beautiful shot of morphine to ease the pain, they strapped me into a stretcher to avoid any movement and lifted me directly out of the gorge and on a direct flight to Pannawonica, some 50 kilometres away, with Kim at my side. At Pannawonica I was transferred to an RFDS fixed-wing aircraft — with state-of-the-art emergency equipment — for the trip to Perth. I don’t remember much about the journey, as they gave me more juice in the veins. I do vaguely recollect the aircraft’s throbbing vibration and rushing air. I also remember having a hazy understanding that this was serious, because my feet were numb and it was hard to move them.

The aircraft landed at Perth’s light aircraft and training airport in Jandakot. I had flown out of it at first light on many a cool, fresh morning, heading back up the coast to mustering camps all over the Pilbara and Gascoyne after getting my helicopter serviced. The media were at the airport when we arrived. I later saw a video of the evening news showing me being wheeled into an ambulance that was waiting to take me to the hospital.

Only one piece of my aircraft ever made it out of that gorge intact. My friend and business partner, the late Jim Adamson, who was then farming at Eneabba, managed to locate the wreck after much difficulty, with the efforts from some kind helpers like Trevor Grover. They discovered that one rotor blade was not damaged at all during the accident. It showed that I must have flared back strongly, in correct engine failure procedure, as I wrestled my machine onto the rocks at the base of the gorge. Jim cut the undamaged rotor blade off the machine, took the wreck home on a trailer, and mounted it on the wall of his den. It’s the only surviving memento of R22 UXK — Uniform X-ray Kilo, which left its few remains in a deep gorge 10 kilometres east-south-east of Mount Farquhar in the Pilbara, Western Australia. ■

The Flying Bushman by Greg Keynes (Gelding Street Press, $29.99rrp) is available at all good bookstores, BIG W and Target

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Greg Keynes grew up on a family property in the Murchison region of Western Australia. Working as a pastoralist and chopper pilot in the early ’80s gave him the unique opportunity of seeing only places that could be reached by helicopter, much of the Pilbara, Gascoyne and Murchison regions along with the world heritage listed Shark Bay. He still travels the regions of WA continuing to write and working in various roles and keeping in touch with his three children and three grandchildren.

By GREG KEYNES

For the full article grab the October 2020 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.