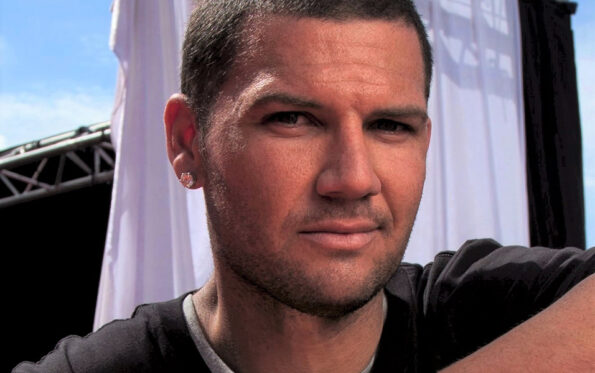

They say true champions eat pressure. If that be true, for 20 years CHAD REED chewed it up, spat it out and asked for more – and more. We take a look back at the legendary Aussie motocross and supercross racer’s illustrious career…

When Chad Reed came into this world, Supercross had been around for a decade. Twenty-years later he would become one of its great legends, and hold a special place as the only rider from the southern hemisphere to win the Supercross world championship.

Like many of his generation, Chad Reed started out aboard a Yamaha PW50. When he showed promise the Reed family moved to a property outside Kurri Kurri, where they lived in a caravan because they couldn’t afford a house. Proud of his Indigenous heritage, young Chad was touched by a burning ambition that would light up the sky. Former pro rider Danny Ham remembers practising with 14-year-old Reed, who left school in Year 9. “Chad didn’t really act like a junior,” Ham says. “He was already riding as if he wanted to beat us. He really was on a mission and knew exactly where he wanted to go and what he wanted to achieve.”

When Reed joined Suzuki and turned pro aged 16, the team practised at the aptly named Crazers near Newcastle. “It was this bad-ass, natural-terrain track,” Chad told former pro racer Lee Hogan. “In one week, I went through three practice bikes. In two of those days, I went through two brand-new bikes.” It’s when you hear stories like this that you begin to understand how Chad Reed thrived in the dog-eat-dog world of American Supercross, the epicentre of the sport and home to its world championship.

How tough is American Supercross? It pays to go back to the sport’s beginnings. The first big-time stadium motocross was staged at the Los Angeles Coliseum in 1972. Riders blasted through famous arches before making the big jump down to the infield as the sun-drenched moto rats in the bleachers lapped it up. Promoters called it the Superbowl of Motocross, later truncated to Supercross. After the huge success of the 1973 event, Supercross spread around the globe.

It also pays to understand why American riders became almost unbeatable, further underlining Chad’s remarkable success. Before Supercross took off in the mid-1970s, American motocross riders were schooled on their own turf by imperious European champions. “I remember when Pierre Karsmakers first came over, we almost got into a fist fight down in Florida,” Kawasaki USA factory rider Jim Weinert remembered. “I was going for first American and this guy was running into me and things. I heard him yelling and screaming and I said, ‘Oh, wow’ and let him pass. He came over to me after the race and says, ‘You should have moved over. I’m the Dutch champion and I’m faster than you’ and all this, and I’m going, ‘Hey, I don’t give a damn who you are! I’m out here racing trying to be first American!’”

For such a proud sporting nation, this would’ve been hard to take. But the Americans were smart. They learned from the Europeans and began schooling them. The best teenage prospects were signed to extraordinary contracts. The son of a Californian fireman, Marty Smith inked cool a deal with American Honda in 1974 when he was aged 17. His high-school ride was a Porsche 930 Turbo, a 911 his back-up. With so much at stake, ruthless team tactics came into play. When one-time boxer Rex Staten joined Team Honda, he’d sidle up to Smith before each race and ask, “Which one of dem guys do you want me to take out?”

The riches in American Supercross drove an intensity to win greater than any other theatre of motorcycle racing. It stepped up when Bob Hannah hit the pro ranks a year after Marty Smith. As he sat beside his old nemesis in a 2007 documentary, Hannah said he hated Smith because he had snatched the 1977 AMA 125cc title away from him and the US$50,000 championship bonus that went with it after Hannah broke a throttle cable. Asked what drove him, Hannah said, “I came from the desert, Jimmy Weinert came from a junkyard. If my dad was rich, I would’ve never made it in Supercross – I would’ve been too lazy.”

Hannah washed dishes, loaded chickens and welded. His opponents never worked a day in their lives. He rode bicycles, jogged and ran track. No-one was fitter. The rags-to-riches mythology, so redolent in boxing, has been part of US Supercross ever since.

Yamaha surprised pundits when it signed 19-year-old Hannah, who was unknown outside SoCal. But nothing prepared the big names when Hurricane Hannah hit town. He strutted around the start gate and trash talked like a well-worn champ. Looking back, Hannah says, “I was a cocky bastard.” He backed it up with seven US championships and 70 national wins, records that stood for 20 years. It was into this cesspit of greed and cut-throat hostility that Chad Reed stepped into in 2002. It was a cesspit that had spooked other Aussie riders.

Australia’s best motocrosser in the 1980s Jeff Leisk scored an entry into the season-opening US Supercross Championship at Anaheim. He was leading the 250cc last-chance qualifier with just a few corners to go when he was T-boned by another rider. “No rider in Australia would ever make that move,” proclaimed Leisk. “Another time Billy Liles’ bike landed on my head after he tried to clear a monster double jump, breaking my jaw.”

In the late 1990s Chad’s close friend and rival, the late Andrew McFarlane, also tried his luck. It was a humbling experience. At each round there were 200 riders entered wanting to get through to the 20- man final. Dozens of local kids would come out of every little nook, every back block, to have a shot at the big time. “In Australia, there might be five guys you gotta beat to get to the final. In America it was like 30,” McFarlane said.

US Supercross was a tough nut to crack for any foreigner. Reed had won the 1999 and 2000 Australian Supercross Championships, but that meant nothing in America. After a mute response from the US, Chad headed to Europe to contest the world motocross championship, admitting “It’s not as cut throat.” Still, conquering America was the end game. “I didn’t dream of racing in Europe, all I ever dreamed of was going to America.” By 2000 the great Bob Hannah had taken a very dim view of American Supercross. With the exception of seven-time winner Jeremy McGrath, Hannah labelled it “weak and embarrassing”. There were some fast guys on the horizon who would soon change his mind.

Aged 18, Reed finished a brilliant second on debut in the 2001 World 250cc Motocross Championship, including a GP win. It was a minor blimp on the radar in Supercross-crazed America, but allied with his two Aussie Supercross crowns and an ultra-aggressive win over Travis Pastrana, it was enough. Chad made his treasured move to the US in 2002 with the top-ranked Yamaha of Troy team. He dominated the East Coast 125cc Supercross Championship, winning seven of the eight rounds and turning heads at the highest levels. It turned even more heads in Australia. One of its own had won an important Supercross title in America.

Reed signed with the Yamaha factory team to contest the 2003 US Supercross Championship. There were murmurs about this fast and determined kid from Down Under, but nothing prepared them for what happened next. Reed won eight races to Supercross legend Ricky Carmichael’s seven, turning the Supercross world on its head. It should’ve been a fairy-tale start to his US career, but Chad finished seven points behind Carmichael to finish a shattering second. What happened?

“At the beginning of the season I started off so well,’ Chad explained. “I won the first race by 25 seconds. I was the one everybody wanted to beat. I think I kinda got caught up in all that. I didn’t like Ricky. I didn’t like his attitude, so I was racing Ricky rather than racing the track. I just wanted to beat him that bad that I was making dumb choices. In Minneapolis I was two seconds faster than anyone but crashed twice, broke my bike and finished sixth. If I had just played it smart – ran just a second faster than everyone, kept it on two wheels and won the race – it would’ve been my championship.”

Carmichael earlier had a meltdown after he went down in a collision with Chad’s teammate Tim Ferry in Salt Lake City, angrily accusing Ferry of doing’s Reed’s dirty work. Ferry denied the accusation. With Carmichael away focusing on winning one of his seven US motocross titles, Chad made up for the one that got away by dominating the 2004 US Supercross Championship, securing 10 races and never finishing off the podium. He was runner-up to Carmichael in the motocross championship.

Reed’s first US Supercross world crown mirrored Wayne Gardner’s historic win in the 1987 World 500cc Championship, but with an important difference. Australians had been contesting road racing’s Continental Circus for decades. Many top Aussies joined the circus in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, resulting in three world titles. In Supercross, the Americans’ money-hungry intensity was almost too much for any foreigner to handle. It took someone of Chad’s considerable mettle to do it. Before Reed, no Aussie had ever been good enough to run near the front let alone ink a factory contract in American Supercross. Some of Australia’s best made good showings; others were overwhelmed. What Chad’s victory underscores is his sheer self-belief to take on America’s best and beat them.

Reed was the only foreigner to figure at the pointy end in US Supercross from 2002 to 2013, when German ace Ken Roczen became a serious contender. Fellow Aussie Michael Byrne was a factory team rider during Chad’s era, claiming 10 top-three finishes without a race win. There are but a handful of Brazilians, Japanese and other nationalities having a go. The field is 95 per cent USA. In the NBA, foreigners make up 23 per cent of the player population. Chad’s unique success also demonstrates that Immortals have the superior mental and learning skills to evolve into complete athletes. Jeff Spencer is a long-time American physical trainer and sports psychologist who worked with the likes of Bob Hannah and Chad Reed.

In selecting his clients, Spencer says, “What’s important to me is how a rider thinks. There are a lot of people who have willpower and talent but end up going nowhere. When someone has the potential to really understand the dynamics of what it takes to evolve and mature as an athlete and sustain a career, that’s the first thing I look for.” He couldn’t have hoped for a better student than Chad Reed.

After Chad made it in the US with his then fiancée now wife Ellie, he quickly hooked up with Americana. He bought two homes – one in California near Yamaha’s test track, and another in Florida, also known for its myriad training courses. A year or so into his stateside adventure, Reed had picked up a distinctive American accent. Asked how that happened so quickly, he said restaurant waiters had trouble understanding his Aussie twang so he began talking the local lingo. It stuck.

As an outsider, Chad garnered a small but vocal band of American fans. They admired his mojo for coming to their backyard and giving as good as he got against the white-hot locals. By then, the rewards for his achievements were flowing. In a teleconference with Australian motorsport journalists in 2004, Will Hagon casually asked Reed how much he was earning. Most athletes demur on these sorts of questions, but Chad answered Hagon just as nonchalantly.

“Seven million.”

“A year?”

“A year…”

Chad was also asked about the prospect of facing off against the hottest new rider on the circuit, James Stewart, who had replicated what Chad had done – winning the East Coast 125cc Championship. African-American Stewart was a star in the making, able to ride at 11/10ths and somehow manage to stay in control. When it was put to Chad that Stewart’s high-risk style might be a problem on a big 450, Chad agreed, “It could be, it could be…” Chad was eager to find any chinks in the Stewart armour. Why? “Right from the beginning, there was bad blood with James,” Reed said. Both two-time US Supercross Champions, Reed and Stewart would stage many bitterly fought battles over the years, including the first 20-lap final of 2009.

To understand how big the Reed-Stewart rivalry had become, I took in the action at Anaheim Stadium in Los Angeles for the annual opening round of the AMA/FIM World Supercross Championship. The energy of the huge crowd of 50,000 was visceral – even before the racing started. This was US Supercross racing at its zaniest best. Defending Champ Reed had dominated the 2008 AMA/FIM World Supercross title with nine wins from 15 rounds to claim his second crown. Reed had defeated Honda’s workman-like Kevin Windham in 2008, and 2009 was shaping up as a four-way battle between Reed, Windham, Stewart and rookie sensation Ryan Villopoto. It was a mouth-watering prospect, and all the fans knew it. There was extra pressure because after so much success with Yamaha, Reed was now saddling up with Rockstar Makita Suzuki. At 7pm the lights went down and the crowd erupted, and finally it was down to the racing. The support American Supercross fans give their favourite riders and the racing in general is simply unbelievable. From the first heat there were cheers, moans and gasps for every spill, near spill, short jump, block pass, attempted block pass, and anything that looked like leading up to a block pass. A successful block pass – no matter if it was for first or 21st – just about brought the house down.

As the stars lined up for the 20-lap final, the entire crowd stood when the 30-second board went up and it was on. When Reed nailed Stewart on the second lap, the place went bananas. Stewart snatched the lead back next time around and the volume went up a notch. At the height of their scrap, the speed and smoothness with which Chad transitioned from the final jump into a giant berm was other-worldly. Then it all went south.

As the battle reached breaking point, Reed’s front tyre clipped Stewart’s rear wheel. Both riders went down. The noisy crowd went quiet. A dazed Stewart picked up his bike, which was then struck by Windham, who was sent sprawling into the Tuff Blocks. A despondent Stewart couldn’t restart his twisted bike and angrily trudged off. Chad continued with no front brake to claim a gutsy third. By the time Chad was interviewed most of the crowd had gone, but a small band of loyal fans had hung around cheering everything Chad said, especially his declaration to stand on the top box next time. Then Stewart went on a seven-race tear. Determined to peg the Floridian back, the Reed-Stewart enmity turned white hot in Jacksonville, Florida. The pair clashed furiously in the berms and almost collided in the air. Stewart won the 20-lap war. Chad was angry.

On the slow-down lap he grabbed the back of Stewart’s neck after he had stopped to acknowledge his fans. Chad warned Stewart, “Don’t cross jump me! We can take each other out on the ground, you can T-bone me, but cross jumping in the air is not cool!” Then they got in each other’s face on the podium. “Chad was looking at me… looking through me,” remembers Stewart, “and I was staring him right in his eyes just in case he flinched and I had to knock him out.”

The title chase was a close-run thing. Stewart won the 2009 championship by just four points, but Reed captured the always-tough US Motocross Championship with a dominant season-long performance. He also won the Monster Energy Triple Crown. At the Phoenix round the following year, Chad put a regulation block pass on James. They collided, Stewart’s bike landing Reed regularly contested the outdoor US Motocross Championship. The Immortals of Australian Motorcycle Racing · 144 awkwardly on Reed’s left hand. Reed remounted but soon pulled in when he realised there was something very wrong with his broken duke. An enraged Stewart finished 15th. After the race he barged into Reed’s pit and pushed Chad’s bike over.

In 2008 Chad partnered Michael Porra in successfully revamping the Australian Supercross Championship, rebadged Super-X. Chad contested all three years of the series alongside guest riders Carmichael and Villopoto, clean sweeping them. Reed enjoyed enormous longevity in off-road motorcycling’s most competitive theatre. Along the way he survived many crashes, the biggest his horrifying launch from a Millville, Minnesota jump in 2011 that ejected Reed six metres into the air. Landing hard and lying motionless, he amazingly sprang to his feet, kicked his Honda into life and stormed through from 34th to 14th, rival pit crews waving him on.

Over his long career in the US, Reed rode multiple brands – Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki, Honda and KTM. He also owned his own teams. One of his sponsors was the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. Reed went back-to-back in the US Open in 2003-04, won a bronze medal in the 2005 X-Games and secured the prestigious 2007 King of Bercy Supercross in Paris, only the second non-European to do so. He joined greats Pierre Karsmakers and Jean-Michel Bayle as the only non-American winners of the World/US Supercross Championship.

In 2011 he won a race on the way to Team Australia’s historic third place in the annual Motocross of Nations. In 2018 he broke the record for most World/US Supercross race starts, and recorded his 132nd podium in 2019. It took a heavy toll on Reed’s body but not his spirit. In 2006 he underwent a major shoulder operation and had numerous treatments for a torn ACL through 2012–13. In 2019 he suffered eight broken ribs, a broken scapula and a collapsed lung.

As Australia’s only Supercross World Champion Chad Reed stands as possibly its most unique Immortal. His legacy is best summed up by his once-bitter rival Ricky Carmichael: “Chad was such a well-rounded athlete. His strongest traits were his raw speed and his willingness to ride through adversity.” And never giving an inch.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darryl Flack has worked as editor at Australian Motorcycle News, was the Australian correspondent for MotoGP.com and freelanced for Two Wheels, REVS, Cycle Torque, Britain’s Motor Cycle News and US weekly Cycle News. He’s also interviewed the great racers of the world, track tested the latest models at Phillip Island, Sydney Motor Sport Park and Amaroo Park and dabbled in road racing, enduro and trials competition.

This is an edited extract from The Immortals of Motorcycle Racing: The World Champs by Darryl Flack (Gelding Street Press, $39.99rrp) available at Big W and all good bookstores

By DARRYL FLACK

For the full article grab the September 2023 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.