As we gear up for the kick-off to the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, we pay tribute to JOHNNY WARREN, the most pivotal figure in Australian football history. In this edited extract from his latest book, author Lucas Radbourne takes a look at the life and times of the legendary Socceroo and how his revolutionary passion provided Australia’s voice in the global game…

With a single utterance Johnny Warren encapsulated the agony and ecstasy; the moment that defines him is the moment that defines Australian football. He captained Australia to its first international trophy in 1967 and its first World Cup in 1974, and played in its first World Cup match. He won four New South Wales state championships, his final as the team’s player and coach, and he even scored the winning goal in the grand final before substituting himself – but off the field he was one of the most influential footballing figures of the 20th century. He wasn’t just a player, captain and coach but also a journalist, administrator, author, broadcaster, lobbyist and revolutionary. When asked what his defining legacy should be weeks before his death his response was: ‘I told you so.’ The defining moments of every other great Aussie footballer are evidence he was correct.

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

Warren entered Australian football in the midst of a revolution and left in the midst of one. Born in 1943, he was the youngest of three boys in a sixth-generation, quintessentially Australian family that lived metres away from where Captain Cook’s first fleet arrived in Botany Bay. As his ocker autobiography Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters makes clear Warren wasn’t born into football like the European migrants who dominate Australian teams, but his love ran much deeper than Australia’s cultural divide.

He and his brothers Geoff and Ross were typically competitive young boys at a time when street cricket on quiet cul-de-sacs was the rite of passage. ‘Wogball’, as it was widely derided, may never have entered his consciousness if it hadn’t been for a chance visit to watch Croatian club Hadjuk Split – on tour for the city’s booming and fanatical Slavic population – play in Sydney. At only six years of age Warren couldn’t have realised what hooked him that day, but while he and his brothers were excelling in the suburb’s homogenous soccer tedium for teams such as the Botany Methodists and Protestant Churches, he knew a crucible of real football passion was bubbling beneath Sydney’s surface and that it was about to erupt.

By 1959 when he was aged 15, Warren had joined Australia’s best and oldest football club, Canterbury, in the closest thing apathetic Australia had to an organised competition. Australia had just joined FIFA, but the Australian Soccer Football Association (ASFA) – its name an example of its hamstrung interests – was still a stagnant outpost of the English FA and had an amateur board and no national league to officiate, which meant its focus was centred on the New South Wales First Division. By then more than a million post-war immigrants had arrived in Australia from Europe’s football heartlands, but nearly two decades before the end of the White Australia policy the ASFA’s focus was on ensuring the amateur New South Wales first tier remained a whitewashed suburban relic. This forced émigrés to build their own community clubs from the ground up, which they did in spades.

The migrant-backed clubs were blocked from the first tier but made the New South Wales second division into a vibrant, multicultural league. While first division clubs could barely muster 800 people to Sydney stadiums, second-tier sides were attracting 8,000 fans to suburban parks and generating so much revenue they were starting to pay their players. When these increasingly powerful migrant clubs continued to be blocked the revolution began: their owners formed a rebel administration and attracted big deferrers, including Warren’s powerhouse Canterbury, to a breakaway league. There Warren was quickly moulded into a decisive, tactical midfielder by former Hungarian national team performance coach Joseph Vlasits.

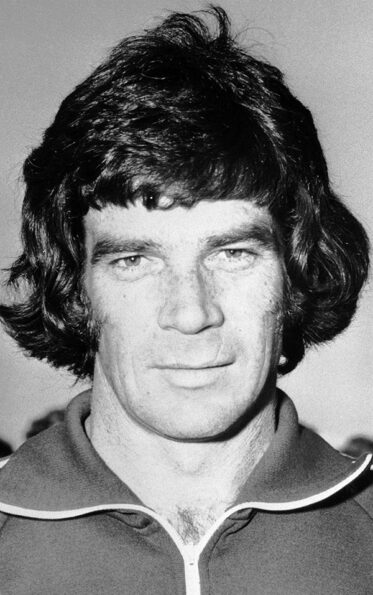

By 1960 17-year-old Warren had become a starlet in New South Wales’s new league, and he scored two crucial goals in a 3-2 semi-final win against APIA as Canterbury won the 1960 New South Wales grand final. Over the next two years Warren spearheaded Canterbury’s dominance and became a commanding yet graceful midfielder with the testament grit and determination that would hallmark his playing career. He had cool, piercing eyes that radiated intelligence, hinting at the mercurial football brain that hid behind them, and a studious, thoughtful demeanour that drew him to the game’s most tactical positions.

He was small and of average build, at just 175 centimetres, but he was tough – never shying away from a challenge – and fair. He’d lash out at an opponent if he thought he’d been wronged, but he was just as quick to turn the other cheek if he’d been decked by a stronger man. His stature and speed made him elegant on the ball, gliding in possession with his head held high and always quick to spot the dutiful lay-off, but he was a ruthless competitor above all else and usually played with a notable grimace slashed across his face.

Vlasits had moved to St George Budapest and helped turn the club into one of the nation’s biggest, so Warren and his brother Ross also moved there in 1963. Warren added an impressive shooting ability to his wide-ranging arsenal at St George and established himself as one of Australia’s finest midfielders. A natural leader, he was not only named club captain but he took over marketing and promotion for the club. Beyond New South Wales, an Australian national team was almost non-existent: Australia had only ever played sporadic friendly matches before the 1956 Melbourne Olympics gave the team a chance for international recognition. Their failure had relegated the team to international purgatory, and by 1965 Australia hadn’t played another country in seven years.

That year, under the guise of football’s new power brokers, Australia was revived to compete in their first World Cup campaign under their first permanent coach, Tiko Jelisavčić. Twenty-two-year-old Warren was called up to the squad but was left out for both qualifiers as Australia was dismantled by North Korea and dumped out of qualifying. It was a nightmare: the Australians hated Jelisavčić and were ridden with diarrhoea and other illnesses from their first trip abroad. Warren witnessed Australia’s disastrous reintroduction to global football from the sidelines, but here in the stench, hatred and humidity was the real beginning of the Socceroos.

Jelisavčić turned to Warren to remedy Australia’s disorganised midfield, and he started his international debut against Cambodia two days later in front of 20,000 hostile fans in Phnom Penh and had an instantly calming effect. Australia’s results improved markedly with Warren but the baptism of fire continued: in just his third match, against Taiwan, the game descended into a riot. Taiwanese fans stormed the team’s dressing room and Warren and his teammates were narrowly saved by riot police. They fled back to their hotel and hid under the tables while fans threw rocks through their windows.

THE VIETNAM WAR

Warren was reunited with Vlasits when the latter took charge of the national team in 1967, and his team was handed the greatest test of its career. The Socceroos were heading to war, at the bloodiest height of Vietnam, as a propaganda exercise to support the Australian troops. The South Vietnam Independence Cup had been held in Saigon each year since 1961, but the Australian military had arranged Australia and New Zealand’s involvement as a public relations exercise. It was the third tournament in Australia’s history, and the team had only played four competitive matches. Warren didn’t realise he had been ‘blindly steered’ into propaganda until years later, but the seriousness of their situation was immediately obvious: “I can remember some of us playing billiards in the mess hall one night when we suddenly heard machine guns firing,” Warren wrote in his autobiography. “All of the players were under the table in the blink of an eye.”

Soon after they arrived Viet Cong soldiers were caught breaking into the hotel with explosives. Australia’s training base was next to a minefield and it was the middle of the monsoon season, so the Socceroos trained on the roof of their hotel, where players would also go at night to watch the aerial bombs exploding in the distance. The hotel’s owner had stolen their food vouchers, leaving the entire team eating ‘substitute ham’, and Warren’s teammate Stan Ackerley was hurtled across the room when he was electrocuted by a power socket. Soldiers with mine detectors walked through the stands during matches, but in the middle of this hell – at 25 years of age and with just six international appearances – Vlasits thrust the Socceroos captaincy onto Warren’s shoulders. At night Warren slept near the shower, the safest place during an attack, but during the day it was his responsibility to guide the young Australian team – whose members’ average age was just 22 and many of whom had friends fighting in the war – to prove that Australian football could be taken seriously, in the most horrendous of conditions. His captaincy proved to be an incredibly apt decision.

Warren played every minute of every match. He scored in the opener as Australia beat New Zealand 5-3, then scored again in the second game to beat the South Vietnamese 1-0 in front of 40,000 fans. Once again riots ensued, and tear gas streamed onto the pitch. South Vietnam’s president visited his national team at half-time to offer them money if they won, but there was no stopping Warren’s side. They smashed Singapore 5-1 and scraped past Malaysia 1-0 in the midst of more on-pitch brawls and crowd violence for a shot at Australia’s first international trophy in the final against South Korea.

At home the tournament was almost completely ignored, but when Warren led Australia onto the pitch for that final match the crowd that had been so hostile up to that point were cheering them on like the home side. “I can still remember the sensation of hairs standing up on the back of my neck as I stood in the tunnel,” Warren wrote. Composed as ever, he scored the crucial go-ahead goal and steered his side to a 3-2 win. “It was one of those moments that I knew I was going to remember for the rest of my life.”

Warren and his teammates, who had to take annual leave from their day jobs to take part, were paid $50 per week for their services, and because they won the tournament they were allowed to keep their tracksuits. Warren was aged 25, an amateur two years into his national career, and he and his team had been spat at, cheated, sickened, pelted with bottles, nails and rocks, had their legs broken and their dressing rooms stormed and their hotels bombed and shot at. They’d survived multiple war zones, attempted murders, snakes, food poisoning and electrocutions. Barely anyone cared, and many back home actively derided them. They had done it all while sacrificing money, opportunities and relationships to the detriment of day jobs and young families.

THE CURSE

The Socceroos’ first trophy was a watershed moment for Australian football, and it began the greatest period in Warren’s career. By the end of 1967 he was the most important player in the national team and had played 14 of their 16 matches since his debut. He’d led Australia to success on the world stage, and now back home at St George he was glimpsing how phenomenal football in Australia could be. St George was a stable, successful club and a pillar of their community, even operating their own licensed bar and venue. Rather than rest on their laurels, however, the club always wanted more. In Warren’s first six seasons they made five grand finals but lost four of them, and finished league runners-up five times.

The near misses ignited a burning ambition, and at a time when many Australian teams were delighted to lure ageing émigrés St George developed their own football talent. They cycled through coaches in search of a true innovator, and found two consecutively in future Socceroos coaches Frank Arok and Rale Rasic. Both coaches demanded a new level of discipline and professionalism, implementing modern training methods and controlling their players on and off the pitch. Warren called Arok the “first real manager in Australian club history” and became increasingly confident and skilful in possession, developing a trademark array of feints he used to devastating attacking effect. St George was one of the country’s most dominant teams for Warren’s 11-year spell, and he guided the club to three New South Wales titles and six grand finals and two Federation Cups.

In 1965 Australia only had to beat one opponent to qualify for the World Cup, and they’d failed. In 1969 they had to beat four across nine games, but Warren’s public demands for greater support were beginning to have an effect. Over 30,000 people watched Australia beat Greece in Sydney that year, sending Warren’s side into qualification on a high. The squad of part timers left a scorching Sydney summer on a 20-hour flight to freezing Seoul, but three days later they beat Japan and South Korea back to back – again to smashed bottles and a police escort.

They flew to Africa for a play-off against Rhodesia, and it’s there that Warren’s story becomes a little unusual. He was ruled out sick from the first match and a wayward Australia struggled through two stagnant draws, and the story goes that the Australians hired a witch doctor on the advice of a local journalist to curse the Rhodesians. Warren dominated the next match, scoring in a 3-1 win to send Australia through. The spell caster demanded $1,000 payment but the Australians refused and left the country, and the furious shaman cursed the Socceroos. Whether the story is true or not, Warren believed it wholeheartedly and Australia lost both their final qualifiers against Israel to end their World Cup hopes.

JOHNNY’S HONOURS

New South Wales First Division: 1960, 1967, 1971, 1974

Federation Cup: 1964, 1972

Member of the Order of the British Empire: 1974

Sport Australia Hall of Fame: 1988

Football Federation Australia Hall of Fame: 1999

Australian Sports Medal: 2000

Australian Centenary Medal: 2001

Order of Australia: 2002

FIFA Centennial Order of Merit: 2004

Alex Tobin Medal: 2008

THE FIRST WORLD CUP

Back home in 1971, Warren captained St George to his second Australian football milestone when they were invited to an international tournament in Tokyo against Japan’s senior and reserve national sides and Danish club champions BK Frem. He led St George to a draw with Japan, thrashed the Danes 3-0 and then destroyed Japan’s reserves 6-2 to win the tournament in style. As captain Warren had now won the first international trophy for an Australian club and for the Australian national team, but that same year he suffered an innocuous knee knock for St George that tore his anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and shattered his career at its peak. It was a devastating injury that semi-professional players rarely returned from in the 1970s, but after 15 months of rehabilitation he fought to return to the Socceroos.

Rasic had replaced Vlasits as national coach and believed the ACL tear had weakened Warren as a player. Fearsome defender Peter Wilson had taken his captaincy and Warren’s midfield role was usurped by Jimmy Mackay, who was the same age and also had a thunderbolt shot in his arsenal. After playing 29 of the Socceroos’ previous 34 matches, Warren appeared in just eight of their next 19 before his retirement. His impact had already been widely acknowledged – he received a Member of the British Empire award in 2003 – and it was hard to believe he could be replaced, but Rasic was the strongest-willed coach Australia had ever had, a trait that got him sacked by Soccer Australia immediately after the 1974 World Cup. Warren sat on the bench as a Mackay thunderbolt against South Korea secured Australia’s first qualification for the 1974 World Cup.

By then, 31 years of age, Warren played just 44 minutes of Australia’s four warm-up friendlies but, given his extraordinary achievements to make it this far, few were surprised when he walked out onto the pitch to start Australia’s first World Cup match against East Germany in Hamburg in front of hundreds of millions of television viewers across the world. Australia had never played a team of this calibre, let alone on such a momentous occasion, but they exhibited the same grit and determination that Warren had instilled in the side in Vietnam. For Warren, however, the curse returned: he suffered a nasty foot injury against the East Germans, and while he endured to finish the game it was the last match he ever played for the Socceroos.

THE WARREN REPORT

NAME: John Norman Warren

BORN: May 17, 1943

HOME TOWN: Sydney, New South Wales

MAJOR TEAMS: Australia, Canterbury-Marrickville, St George Budapest

POSITION: Midfielder

SOCCEROO CAREER: 1965-1974 (42 appearances, seven goals)

CLUB CAREER: 1959-1974 (200+ goals*)

*Not all goals have been recorded.

THE LEGACY

Warren returned from the World Cup to find St George near the bottom of the ladder, and he took over the coaching reins in addition to captaining the side. He commanded a startling turnaround and his side won eight of their last nine matches to make the grand final, in front of a boisterous Sydney crowd. In the final stages he dispossessed an opponent in the central circle and feinted and burst past another defender before scoring the winner with the outside of his foot from the edge of the box. Leading until the end, he substituted himself off the pitch, ensuring his own fairy-tale finish.

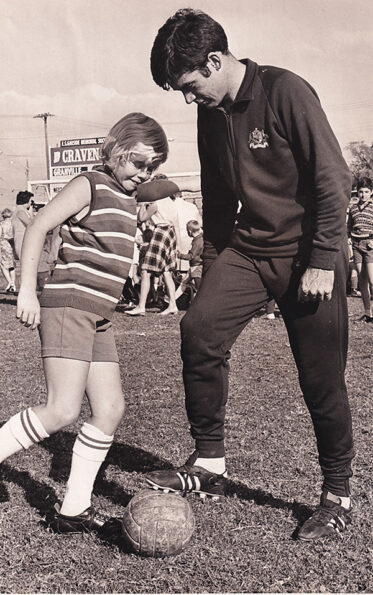

Although Warren’s playing career was over, his football legacy had just begun. The irony of his autobiographical title is that Australian football in the 1960s and 1970s was populated by some of the fiercest athletes Australian sport has ever seen: émigrés from war-torn Europe and hardened Brits spat out by the English football system, all thrown together on sun-baked pitches with little control or volition. He dedicated himself to shifting Australian football’s reputation and encouraging the next generation and helped establish and then coach a football club in Canberra, where he ran famed training camps for Australian youth.

His greatest impact came at SBS, where he and broadcast partner Les Murray, nicknamed ‘Mr and Mrs Soccer’, became the public faces of Australian football for three decades. Warren was an astute analyst, passionate commentator and tireless advocate who legitimised Australian football to the masses. He hosted the television program Captain Socceroo, which inspired many of the Socceroos’ future golden generation, and wrote or contributed to eight books on football in addition to weekly newspaper columns.

His crying on live television after the Socceroos’ disastrous loss to Iran in 1998 symbolised the suffering of all Australian football fans. “He was the embodiment of Australian soccer’s struggle and the struggle of life,” Andy Harper told The Sydney Morning Herald. “He demystified multiculturalism for Australia and opened up corners of the world that Australians didn’t even know existed.”

Warren was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2002, the same year he delivered one of his greatest legacies: the Report of the NSW Premier’s Soccer Taskforce. After three months of writing he listed 11 recommendations, from as symbolic as calling the game football to as major as establishing the A-League. These recommendations became the foundation of the 2003 Crawford Report, a federal government investigation into the systemic corruption and mismanagement of Soccer Australia. Warren was the only football-related member of the committee. The Australian Sports Commission threatened to withdraw funding for the organisation, and the resulting changes were tremendous. The Soccer Australia board retired en masse and Football Australia was born.

A frail Warren was presented with FIFA’s Centennial Order of Merit in 2004 alongside Pele and Franz Beckenbauer. His last public appearance was at the announcement of the A-League in April 2004. He died seven months later, exactly 12 months before the Socceroos qualified for their first World Cup in 32 years in front of 86,000 fans and a giant banner reading “I told you so”.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lucas Radbourne thinks he could have gone pro if it hadn’t been for his bad knee. Instead, he settled for being an editor for FourFourTwo Australia, FTBL, The Women’s Game and Beat Magazine. These days he’s planning to spend most of his money on booze, birds and fast cars. He heard once that the rest you just squander.

The Immortals of Australian Soccer by Lucas Radbourne (published by Gelding Street Press, rrp$39.99) is available at all good book stores or online at geldingstreetpress.com

For the full article grab the November 2022 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.